This manifesto

is presented, unedited in its original form.

It was distributed locally at public forums and to various individuals

around the country in 1972. It

was sent to Leonardo, International Journal of the Contemporary Artist

in 1973 and was accepted byEditor, Roger Malina for publication. Working with Mr. Malina, the text was edited and rewritten to conform

with Leonardo Journal standards. The

manifesto was re titled and published: Leonardo, Vol. 7. No. 2 Spring, 1974, Pergamon Press, “On Stereoscopic

Painting” pages 97 – 104. Roger

Ferragallo, 7/12/2000

(Reformatted for Web Display)

A MANIFESTO

DIRECTED TO THE NEW AESTHETICS

OF STEREO SPACE IN THE VISUAL

ARTS AND THE ART OF PAINTING

November 12, 1972

© Roger Ferragallo

Painting is reborn…….Enter

the new awareness of Stereo Space and a New Aesthetics …….The centuries

long conquest of plastic forms within a monoscopic pictorial space is

ended……..A new era lies ahead for the visual arts…….The living third dimensional

space-field awaits its birth. It

asks nothing more than the trance-like stare of the middle eye to invoke

Cyclops to waken from his 35,000 year sleep.

This primeval giants reward will be the sudden revelation and witness

to the dematerialization of the picture surface into an aesthetics of

pure space where visible forms will materialize and release themselves—forms

that are suspended, floating, hovering, poised, driving backward and forward,

near enough to touch and far enough away to escape into the void………...So

now enter a new aesthetic empathy, meditation, subjective intensity and

an unparalleled form-space generation and communication.

All of this exciting

injunction could have been declared 134 years ago had it not been for

the invention of photography. But

at that time, 1838, the full investigation of form within the limits of

the monoscopic surface had not yet been fully realized:

the genius of Cezanne, Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, Balla, Mondrian,

Kandinsky, Moholy-Nagy, Pollach and Escher lay ahead.

Awaiting the future, too, would be the subjection of the picture

plane to the forces of sculpture with such explosive consequences that

our galleries and museums are graveyard and garden of plastic visual forms

rented from the ribs of paintings. Looking back to 1838, one gazes with astonishment

at the paper presented to the philosophical Transactions of the Royal

Society of London on June 21, 1838 by Charles Wheatstone. Entitled “ON SOME REMARKABLE AND HITHERTO UNOBSERVED,

PHENOMENA OF BINOCULAR OF BINOCULAR VISION”, this paper must now be recognized as describing

one of the most remarkable techno-visual discoveries in the 35,000 years

of the History of Art. This paper

revealed a discovery as stunning as were the great polychrome visions

painted by Magdalenian artists. Its

contents were as innovative as was the first portrayal of overlapping

planes and depth by the great neolithic cultures.

It’s thesis was a powerful as the conquest of the third dimension

rendered by Greek and Pompeian painters as focused in the Villa of Mysteries—yes,

as revolutionary as was Brunelleshi’s invention of the laws of perspective

and Campin’s and Van Eyck’s development of the oil medium in the early

hours of the 15th century—even as momentous for our twentieth

century as were the shattered and re-combined forms of the Cubists and

the pioneers who explored “simultaneity”, psychic symbolism and free association.

(1)

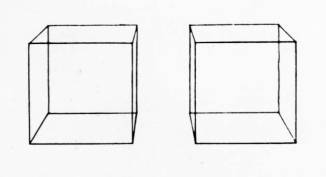

Returning to 1838, to Wheatstones

stereoscopic drawings in the light of what was to boil out of Paris and

London by Turner, Constable, Delacroix, Corot, Daguerre, Plateau, and

to the oncoming tide of Courbet Manet, Monet, Seurat and Cezanne, one

can be stirred by the lonely singular event portrayed in the stereoscopic

drawing of two cubes by Wheatstone (Fig.1).

If it meant little at the time to artists, too shocked by Daguerres

“sun-pictures” and Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature”, it now means the eclipse

of our monoscopic view of the picture surface as a staging arena for plastic

form and the beginning of a new space aesthetics of air, light, form,

color—all discharged into the openness of windowless space.

Now awakened

from its long sleep, the discovery by Wheatstone of the psycho-optical

consequences of our binocular vision of reality, one sees that this is

but the product of our two spaced-out eyes rendering two different retinal

views of forms in the visual field. Two

views, however, brought into a cyclopean fusion by the mind to render

a profound single spatial awareness of reality—as reality is.

Aware of this phenomenal rendering, Wheatstone wrote:

“It

will now be obvious why it is impossible for the artist to give a faithful

representation of any near solid object, that is, to produce a painting

which shall not be distinguished in the mind from the object itself. When the painting and the object are seen with

both eyes, in the case of the painting two similar pictures are

projected on the retinae, in the case of the solid object the pictures

are dissimilar; there is therefore an essential difference

between the impressions on the organs of sensation in the two cases, and

consequently between the perceptions formed in the mind; the painting

therefore cannot be confounded with the solid object.” (2)

Despite this

remarkable achievement and prescience of Wheatstone, all of the progress

and innovative developments of painters to his time (and yes, ours) to

arrive at “a painting which shall not be distinguished in the mind

from the object itself”—all were doomed to failure in spite of the

incredible monoscopic illusionist successes of Van Eyck, Raphael, Heda,

Zurbaran and Harnett.

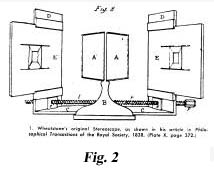

It remained for Wheatstone to make the singular

discovery that when we view a cube which is set before us and when we

close one eye and then the other, it is apparent that we see two distinctly

different appearances of the cube. While

corroborations of this fact can be traced back through illustrious writings

of Francis Agullonius, Baptista Porta, Leonardo Di Vinci, and even more

into the remote past—to Galen and Euclid, it remained for Wheatstone to

produce the first stereo- synthetic form and the means to achieve a conscious

stereopsis of it in the mind. It

must have been an extraordinary moment of insight when he realized that

when two outline drawings representing the binocular view of a cube might

become fused together, then this image would be accepted by the mind as

a concrete solid existing in the same real spatial sense—as though one

could reach out to touch it. Indeed

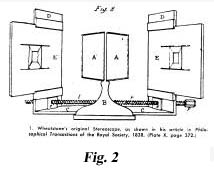

this was the case. Wheatstone devised a simple mirrored apparatus

to aid the cause of fusing his three-dimensional drawings. He called this device a Stereoscope

(Fig.2). Wheatstone does not appear

to discuss, at any length, the direct vision viewing of stereo pairs,

nor does he suggest that he has delivered to the visual arts a new revolutionary

method. He speaks to this, however,

in these words: It remained for Wheatstone to make the singular

discovery that when we view a cube which is set before us and when we

close one eye and then the other, it is apparent that we see two distinctly

different appearances of the cube. While

corroborations of this fact can be traced back through illustrious writings

of Francis Agullonius, Baptista Porta, Leonardo Di Vinci, and even more

into the remote past—to Galen and Euclid, it remained for Wheatstone to

produce the first stereo- synthetic form and the means to achieve a conscious

stereopsis of it in the mind. It

must have been an extraordinary moment of insight when he realized that

when two outline drawings representing the binocular view of a cube might

become fused together, then this image would be accepted by the mind as

a concrete solid existing in the same real spatial sense—as though one

could reach out to touch it. Indeed

this was the case. Wheatstone devised a simple mirrored apparatus

to aid the cause of fusing his three-dimensional drawings. He called this device a Stereoscope

(Fig.2). Wheatstone does not appear

to discuss, at any length, the direct vision viewing of stereo pairs,

nor does he suggest that he has delivered to the visual arts a new revolutionary

method. He speaks to this, however,

in these words:

“For

the purposes of illustration I have employed only outline figures for

had higher shading or coloring been introduced it might be supposed that

the effect was wholly or in part due to these circumstances, whereas by

leaving them out of consideration no room is left to doubt that the entire

effect of relief is owing to the simultaneous perception of the two monocular

projections, one on each retina.. But

if it be required to obtain the most faithful resemblances of real objects,

shadowing and coloring may properly be employed to heighten the effects. Careful attention would enable an artist to draw and paint the two

component pictures, so as to present to the mind of the observer, in the

resultant perception, perfect identity with the object represented. Flowers, crystals, busts, vases, instruments

of various kinds, etc., might thus be represented so as not to be distinguished

by sight from the real objects themselves” (2) (Fig. 3).

Were it not for

the invention of the photograph these words might have fired the new spatial

art. One might imagine where this

revolutionary concept would have taken Manet, Monet, Seurat or Cezanne. Within six months of delivering his paper to

the Royal Society, Wheatstone had already conceived of asking Fox Talbot

and Henry Collen to provide him with photographic Talbotypes of statues,

buildings and people. Since then

photography has continued to utilize this astonishing discovery.

We must return

back to the moment before the photographic stereo view of reality overwhelmed

Wheatstone and his contemporaries. A

mere seven score years is but a moment in the strata of history—but the

soil is now ready. Today we are

dealing with the possibilities that entire orchestrations of color forms

can be made to exist synthetically in a binocular space-field that

is itself consonant with reality. The

phenomenon of the Cyclopean Eye which miraculously renders our visions

of the pristine, sylvan landscape now prepares us for the new stereoscopic

art. Oliver Wendell Holmes, speaking in the year

1859, (Atlantic Monthly) might as well have directed these words to us

when he wrote:

“Nothing but

the vision of a Laputan, who passed his days in extracting sunbeams out

of cucumbers, could have reached such a height of delirium as to rave

about the time when a man should paint his miniature by looking at a blank

tablet, and a multitudinous wilderness of forest foliage or an endless

Babel of roofs and spires stamp itself, in a moment, so faithfully and

so minutely, that one may creep over the surface of the picture with his

microscope and find every leaf perfect, or read the letters of distant

signs….just as he would sweep the real view with a spyglass to explore

all that it contains.” (3)

Though Holmes

was referring here to the art of stereo-photography, this augury is but

a stone's throw to an art of pigment, dye and ink.

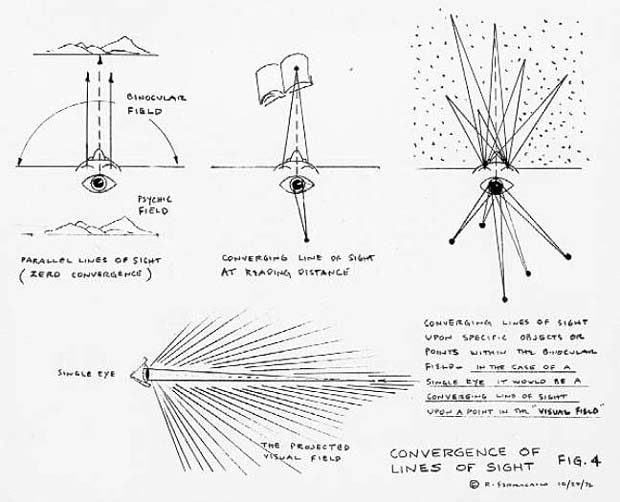

When the art of stereo-drawing and binocular disparity is mastered,

one is within reach of a totally new aesthetics;

an art of undetermined power—radically different, and basically

new, whose only requirement will involve a capacity at everyone’s disposal

who has normal binocular vision—the converging of lines of sight.

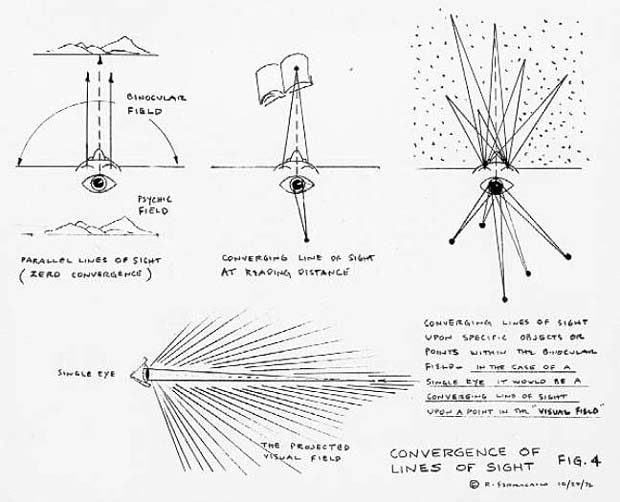

This will require some examination of our

binocular powers of vision. Two

distinctly different projections of outside environments, falling upon

the active retinal screens of both eyes cause the unexplainable, as yet

hidden, power of consciousness to form a coherent, corespondent synthesis

of the outside environment. When

we fix our eyes, in a relaxed manner, upon the most distant reaches of

a landscape, both eyes, are said to be staring with parallel lines of

sight. (Fig. 4) Each

eye, under these circumstances, is rendering its own different view of

what might be a line of mountains. We

may say that in the “mind’s eye” the images of the mountains have coalesced—fused

into one image; as though we had

an eye in the middle of our foreheads. In a sense, metaphorically, we have; we will refer to this as the

cyclopean eye. (Hering, “oeil de cyclope imaginaire,” 1867) This will require some examination of our

binocular powers of vision. Two

distinctly different projections of outside environments, falling upon

the active retinal screens of both eyes cause the unexplainable, as yet

hidden, power of consciousness to form a coherent, corespondent synthesis

of the outside environment. When

we fix our eyes, in a relaxed manner, upon the most distant reaches of

a landscape, both eyes, are said to be staring with parallel lines of

sight. (Fig. 4) Each

eye, under these circumstances, is rendering its own different view of

what might be a line of mountains. We

may say that in the “mind’s eye” the images of the mountains have coalesced—fused

into one image; as though we had

an eye in the middle of our foreheads. In a sense, metaphorically, we have; we will refer to this as the

cyclopean eye. (Hering, “oeil de cyclope imaginaire,” 1867)

Vision is mainly,

however, concerned with convergence.

Now as we look with both our eyes at specific objects located within

the binocular field, from six inches to as far as we can see, we are rotating

our eyes to converge two lines of sight upon an object.

Our eyes can accommodate to focus and converge upon any form, anywhere

in the visual field, with fixed attention, or with saccadic strokes. A single eye can do just as well, in the sense

that the visual field is formed by the eye into a great cone of space—like

a giant cyclone light flux 150 degrees wide. The eye of the cyclone, at its apex corresponds

to the fovea of the retina which is the seat of our sharpest vision.

One has a view of it by imagining a fine pencil of laser light

emerging from the vanishing point of some self-directed linear perspective.

All of the visual cues available to painters today to suggest distance

and depth are entirely the domain of the single eye. But when both of these great visual cones converge upon an object

in space—a profound property of vision emerges: stereopsis. Two retinal

screens, not one, signal the cascading light show from outside the lens

window of the eye to the cyclopean eye which opens to consciousness a

psychic field consonant with the binocular field. (Fig. 4)

The more conscious

we are of the spatial distinctions within the vastness of this fused,

binocular-psychic space, the richer it can be said is our “stereopsis”. The key to our sensation of stereopsis is through two well known

factors acting together: Convergence

and Disparity. (4)

When both retinal

cones converge upon a specific object in space, the eyes have found the

range, so to speak, and the mind computes an accurate sense of distance. Binocular convergence involves the fact that

our eyes are separated by a width of about 2 ½ inches. With this width serving as a base, our two

lines of sight converge upon specific objects in space, spraying a profusion

of triangular fixations upon them. With

each fixation, a train of focal adjustments for each eye lens issues simultaneously

as the eyes fix upon a distant aircraft, a nearby tree, or an ant passing

over a leaf. The brain gives a

critical evaluation of both factors and computes its sense of definition,

distance and scale. Acting in

concert with triangulation and focal accommodation is the brains computation

of the shifted differences observed in objects that are seen separately

by the left and right eye. This

is called binocular or retinal disparity.

(Parallax-displacement-shift)

It is absolutely critical and important to our sensation of depth

perception. By examining Fig. 5, No. 1 to 5, one can easily

ascertain the fact that we see everything double except for the area around

the foveal point of convergence of the primary lines of sight. Unconsciously, we simply pay little attention

to this double vision unless we make a point to observe it as indicated

by the diagrams. The mind however,

compares and regards this rain of light bombarding the retina, with all

its subtended angles and shifts of position, with computed finesse. Disparity as we shall see, will be at

the center of the new space aesthetics.

Connected with convergence and

disparity, and important to this thesis, will be the realization that

just as one has the ability to converge upon these words, any one can

just as easily acquire the skill of crossing the visual axes in an

imaginary space. (5) This

essential factor, combined with disparity, opens the way to learning

the methods and skills in both the construction of primary binocular

forms and the viewing of them. The

illustration in Fig. 5, No. 6 suggests that a left and right line of

sight can be

brought to cross in space at

an imaginary point (cv) to fuse two objects (A & B), at a

distance, into one. This imaginary

point is obtained by fixing the lines of sight at about reading distance,

usually by staring ahead (obtaining a fix) through the index finger.

Obtaining such a “fix” upon the tip of the index finger will

cause any pair of objects in the distance, two balls for example lying

along the same path of sight, to coalesce into one new ball at the center

position. The two original balls

remain in sight, as two residual-phantom images. This can all be very easily demonstrated another

way by using only the fingers. Simply

raise the forefinger and middle finger of one hand into the familiar

V sign, at arms length. Bring

the tip of the finger of the opposite hand between the eyes at about

reading distance and stare ahead. By

closing one eye and then the other, one can corroborate precisely what

is illustrated in Fig. 5, No. 6.

As

a further consequence of this discussion of disparity and convergence

it will help to look at Fig. 6 which illustrates the two distinctly different

methods of viewing binocular constructions. The method of parallel lines of sight

(staring fixedly ahead beyond the pairs) and the method of crossing

lines of sight are contrasted. Viewing

stereo constructions by means of parallel sight limits picture size (2

½” separation between image objects) which is a physical limitation based

upon the interocular separation of the eyes.

This special kind of vision, then, limits itself to small scale

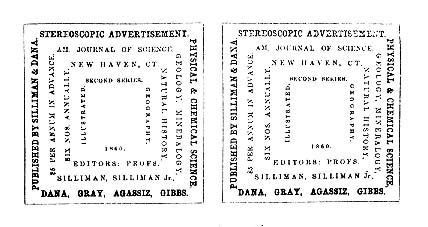

pictures and figures. An interesting

example of the early use of this idea, published in 1860, is the advertisement

shown in Fig. 8. This example

serves to demonstrate the arrangement of words as merely decorative as

distinguished from the expressive-spatial interrelationship found in 3-D

Concrete Poetry. (6) As

a further consequence of this discussion of disparity and convergence

it will help to look at Fig. 6 which illustrates the two distinctly different

methods of viewing binocular constructions. The method of parallel lines of sight

(staring fixedly ahead beyond the pairs) and the method of crossing

lines of sight are contrasted. Viewing

stereo constructions by means of parallel sight limits picture size (2

½” separation between image objects) which is a physical limitation based

upon the interocular separation of the eyes.

This special kind of vision, then, limits itself to small scale

pictures and figures. An interesting

example of the early use of this idea, published in 1860, is the advertisement

shown in Fig. 8. This example

serves to demonstrate the arrangement of words as merely decorative as

distinguished from the expressive-spatial interrelationship found in 3-D

Concrete Poetry. (6)

It is the crossing  of

lines of sight that must draw our full attention.

This is of great importance because there is no limit to the

size of images and constructions; nor is there a limit to the distance

from which they may be viewed. Crossing

lines of sight is central to the proposal in this thesis.

It must be noted that both of these methods (parallel and cross

vision) of viewing stereo constructions have quite different properties. This difference will be apparent as you try

to view the constructions in Fig. 6.

You will note an inversion of the spatial figures if you use

one and then the other method of viewing the small figures. The large stereo drawing at the top of the page is impossible to

view with parallel sight because the homologous points are beyond 2

½ inches. With crossed vision

they present no problem. Accomodating

yourself to crossing your lines of sight brings the viewer to within

reach of the new space art—an art whose only of

lines of sight that must draw our full attention.

This is of great importance because there is no limit to the

size of images and constructions; nor is there a limit to the distance

from which they may be viewed. Crossing

lines of sight is central to the proposal in this thesis.

It must be noted that both of these methods (parallel and cross

vision) of viewing stereo constructions have quite different properties. This difference will be apparent as you try

to view the constructions in Fig. 6.

You will note an inversion of the spatial figures if you use

one and then the other method of viewing the small figures. The large stereo drawing at the top of the page is impossible to

view with parallel sight because the homologous points are beyond 2

½ inches. With crossed vision

they present no problem. Accomodating

yourself to crossing your lines of sight brings the viewer to within

reach of the new space art—an art whose only requirement will involve the necessity of staring fixedly at the center

point between the dyptich images of a stereographic construction. (Fig.

7) There will be the essence

of hypnosis in the stare, for it will project one into space to interlock

with the painted color forms until he is no longer outside but virtually

inside—in aesthetic empathy with whatever visual forces have been unleashed

into the openness of space. The act of seeing this new space is simple: You, the viewer, may use a finger as a reference

to crossing your lines of sight, or you may block out the left and right

images with your hands; or use

the suggested cardboard block-out card shown in Fig. 7. You stare—you willfully converge your eyes

at your finger tip and at the same time observe the dual construction

requirement will involve the necessity of staring fixedly at the center

point between the dyptich images of a stereographic construction. (Fig.

7) There will be the essence

of hypnosis in the stare, for it will project one into space to interlock

with the painted color forms until he is no longer outside but virtually

inside—in aesthetic empathy with whatever visual forces have been unleashed

into the openness of space. The act of seeing this new space is simple: You, the viewer, may use a finger as a reference

to crossing your lines of sight, or you may block out the left and right

images with your hands; or use

the suggested cardboard block-out card shown in Fig. 7. You stare—you willfully converge your eyes

at your finger tip and at the same time observe the dual construction

ahead as it

divides into three images. It

is at this instant that you stare at the third central image—you gaze—concentrate—meditate

fixedly upon the center image until it comes on you—and it will—with

the clarity and power of sudden revelation. The painted forms will be seen to exist in

real space, actually and concretely, as if in the nether world of dreams

you have just opened a middle eye—a cyclopean power. Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing in Atlantic Monthly, July, 1861,

in an article titled: “Sun-Painting

and Sun Sculpture” speaks of this faculty:

“Perhaps there

is also some half-magnetic effect in the fixing of the eyes on the twin

pictures, --something like Mr. Braid’s hypnotism……At least the shutting

out of surrounding objects, and the concentration of the whole attention,

which is a consequence of this, produce a dream-like exaltation of the

faculties, a kind of clairvoyance in which we seem to leave the

body behind us and sail away into one strange scene after another like

disembodies spirits.”(7)

When you will

have once raised the lid of the middle eye—the cyclopean power will remain

open and becomes easier—finally effortless.

You will have before you a visual field of immense spatial depth,

an arena where the total of the visual vocabulary will be given the distinction

of reality and life in space. A

powerful intensification of communication—of communion with form. Elements which formerly were locked within

the monocular field are now free to exist above, within, and beyond the

surface upon which the forms themselves are painted.

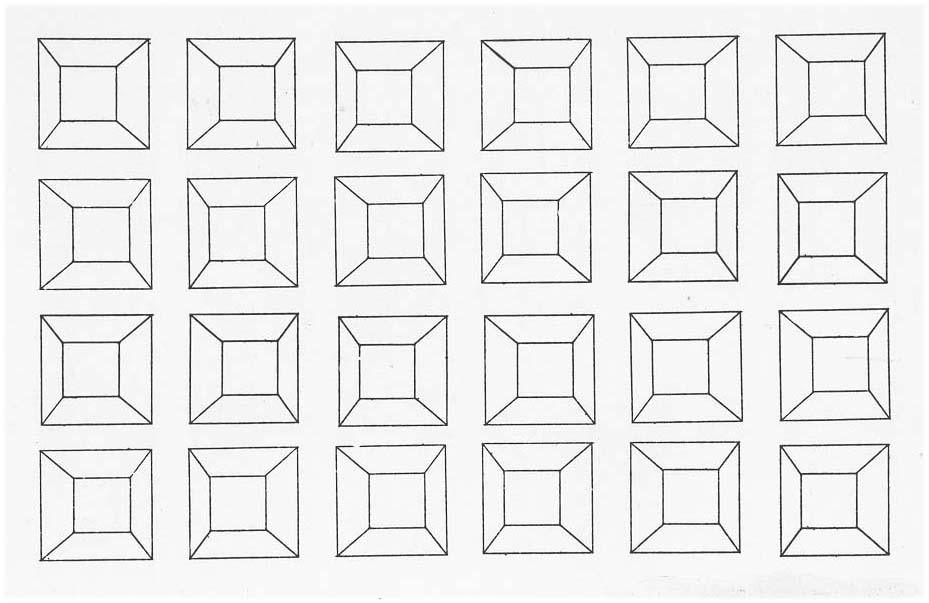

There are no longer any barriers to position or place in stereo

space—no boundaries. Any diptych

pair can be paired with any other to render a sense of boundless repetition

in all directions. (Fig. 9 and

Fig.10) With the simple act of cyclopean fusion even

the very walls of architecture will dissolve away into immense stereo

spatial fields of crystalographic color patterns.

The physical carrier of form, be it canvas, paper, concrete, fresco

will no longer have any meaning. Dot,

Line, Plane, Volume, Space, Color and Texture will orchestrate in open

space where formerly the dynamics of such spatial entities were displayed

in concert with the surface. In

the new aesthetics of stereo-space the surface dematerializes and

evaporates itself into space. It

is quite remarkable that this dematerialization of the picture surface

was described in some detail by Sir David Brewster in his book “On the

Stereoscope” published in 1856. In a Chapter titled: “On the Union of Similar Pictures in Binocular

Vision”, he describes experiments on large surfaces that he covered with

similar plane figures. Brewster

stated:

“If we, therefore,

look at a papered wall without pictures, or doors, or windows, or even

at a considerable portion of a wall, at the distance of three feet and

unite two of the figures, two flowers, for example—at the distance of

twelve inches from each other horizontally, the whole wall or visible

portion of it will appear covered with flowers as before but as each flower

is now composed of two flowers united at the point of convergence of the

optic axes, the whole papered

wall with

all its flowers will be seen suspended in the air at the distance of six

inches from the observer! At

first the observer does not decide upon the distance of the suspended

wall from himself. It generally

advances slowly to its new position, and when it has taken its place it

has a very singular character. The

surface of it seems slightly curved.

It has a silvery transparent aspect.

It is more beautiful than the real paper, which is no longer

seen, and it moves with the slightest motion of the head.

If the observer, who is now three feet from the wall, retires from

it, the suspended wall of flowers will follow him, moving farther and

farther from the real wall, and also, but very slightly farther and farther

from the observer. When he stands

still, he may stretch out his hand and place it on the other side of the

suspended wall, and even hold a candle on the other side of it to satisfy

himself that the ghost of the wall stands between the candle and himself.”

It seems impossible that these words should

lie buried for 116 years. And

it is even more astounding that this marvelous description by Brewster

could possibly have been and still can be an art involving repeated patterns,

continuous friezes, whole architectural assemblages of crystalographic

color-forms suspended in air, existing beyond and beneath a dematerialized

planar surface. Buried in the

19 Century, and clearly within the scope of this statement—of the new

aesthetics, also lie experiments by Brewster, H. W. Dove, and O. N. Rood

on what they called the theory of “Lustre”. This involves the binocular fusion of color

fields giving rise to phenomenological kinds of atmospheric, optical color

mixture. The monocular color fields

of Seurat and color field abstractionists today will pale before the new

possibilities of binocular color fusion.

Returning to Brewster, one cannot underestimate the enormous possibilities

suggested by him. Not only is

he saying that the surface has dematerialized, but that stereoscopically

paired graphic forms can be multiplied n-times-in all directions.

In Fig. 10, one of Wheatstone’s paired drawings has been organized

as a potentially n-crystalographic field—either by the method of parallel

sight or by cross-viewing, you will immediately witness something very

astonishing: One will find that his “Cyclopean” sense, the unconscious, (Gestalt)

or whatever it will eventually be understood to be, will hold the entire field fixated while at the same

time, he (the viewer) is free to direct his eyes to any portion of the

field—to focally converge upon any particular isolated point, figure or

cluster of figures. How does

the mind hold so large a psychic field of visible forms constant

while permitting a foveal examination of details in any direction? It is as though one has induced hypnosis to one level of mind while

permitting another level of mind virtual license. It seems impossible that these words should

lie buried for 116 years. And

it is even more astounding that this marvelous description by Brewster

could possibly have been and still can be an art involving repeated patterns,

continuous friezes, whole architectural assemblages of crystalographic

color-forms suspended in air, existing beyond and beneath a dematerialized

planar surface. Buried in the

19 Century, and clearly within the scope of this statement—of the new

aesthetics, also lie experiments by Brewster, H. W. Dove, and O. N. Rood

on what they called the theory of “Lustre”. This involves the binocular fusion of color

fields giving rise to phenomenological kinds of atmospheric, optical color

mixture. The monocular color fields

of Seurat and color field abstractionists today will pale before the new

possibilities of binocular color fusion.

Returning to Brewster, one cannot underestimate the enormous possibilities

suggested by him. Not only is

he saying that the surface has dematerialized, but that stereoscopically

paired graphic forms can be multiplied n-times-in all directions.

In Fig. 10, one of Wheatstone’s paired drawings has been organized

as a potentially n-crystalographic field—either by the method of parallel

sight or by cross-viewing, you will immediately witness something very

astonishing: One will find that his “Cyclopean” sense, the unconscious, (Gestalt)

or whatever it will eventually be understood to be, will hold the entire field fixated while at the same

time, he (the viewer) is free to direct his eyes to any portion of the

field—to focally converge upon any particular isolated point, figure or

cluster of figures. How does

the mind hold so large a psychic field of visible forms constant

while permitting a foveal examination of details in any direction? It is as though one has induced hypnosis to one level of mind while

permitting another level of mind virtual license.

Seeing, per se,

is a process which is still little understood!

One will find, too, that the more he exercises this psycho-optic

ability, the easier and easier it becomes to fixate both the field and

its detail. After a time, it will seem quite natural to

cross-view synthetic forms as it is natural to converge the eyes normally

upon objects. This suggest the

vista of an aesthetics that will

undoubtedly bring

forth a very powerful (psychosynthesis) transcendental, meditative art. This binocular art may also have within it

the power to bridge the gulf between the traditional Western and Eastern

conceptions of space. Here, then,

will be an aesthetics that will involve the philosophical, historical,

spatial invention of both East and West into an unparalleled new synthesis. The picture surface has only been understood,

up to now, monoscopically, as though we were all inhabitants of some “Flatland”

(9). This is not to say that the

great tradition of monoscopic painting is to be occluded any more than

it is to view the techno-spatial inventions of the last 35,000 years are

suddenly brushed aside. Monoscopic,

flat field, or space-illusionist art whether it be Paleolithic, Medieval,

or of the nature of “The Garden of Delights”, Michelangelo’s “Sistine

Ceiling”, “La Grand Jatte”, “Guernica”; all of these are among the treasured heritage

of the past. The long history

of hard-won innovations of rendering visual illusions upon planar surfaces

is an immense fund of techno-visual language.

From the Aurignacian to the present, the list of spatial invention

is long: vertical position, overlapping

planes, diminution of size, aerial and linear perspective, inverted and

multiple perspective, foreshortening, shadows, texture gradients, optical

illusions, interpenetrating form and space, advancing and receding color

fields, two dimensional space division, illusions of motion and after

images. A stereo art cannot properly

exist without the involvement of these important monoscopic space illusions. What is called for now is the re-integration

of this knowledge with our psycho-binocular powers of stereopsis—a sensing

of the three-dimensional space field that lies both within and without

us. This is both possible now and necessary. Speaking both to the art of pigment, dye and

ink and to the art of light sensitive emulsions—inevitably they must now

be driven together. Stereoscopic

aesthetics will be an arena that will see the plastic forms of the past

100 years fusing into staggering arrays of re-combinations of familiar

and unfamiliar forms, new synthesis, shimmering-lustrous color fields; all existing in air—a space without a canvas

base, paper base or physical carrier whatever.

There will be complete and remarkable deceptions of the physical

and mental eye. The space outside

our heads will match the space inside our minds.

It will mean the discovery of a mental force that will warp two

constructions into one—into single a cyclopean phantom, as though our

primitive, infantile diplopia were being brought into fusion and synthesis.

We are at the beginning of a new era in the visual arts no less

momentous than was our thrust into the depths of space, which was to link

the surface of the earth with the Lunar Sea of Tranquility.

We looked back upon ourselves from that luminous Astral sea with

psychic shock and a compelling awareness of where we really are.

No less are we enthralled by the vastness of inner-space. We can truly be aware that this intensification

between ourselves, this planet “space-ship earth” coupled with our relentless

bombardment of atomic nuclei will all inevitably drive the arts (as we

know them) into totally new perspectives. The time is now. The tools

are here: they exist in the photographic

arena of Holography, Xography, Vectographs, Anaglyphs, polarized stereo

pairs, wide screen stereo-panoramas, stereo-cinematography and stereo-video.

They are before those of us who must now awaken the sleeping cyclops

to reform – and to refashion in paints, dyes and inks, synthetic assemblage

orchestrations of color-forms in a psychic-binocular space.

© Roger Ferragallo 1972

REFERENCES

1 Layer,

H. A., Figurative Photo-Sculpture with 3-D Pointillism, Leonardo 5

55, 1972

2 Wheatstone,

Charles. Philosophical Transactions

of the Royal Society of London,

“On

Some Remarkable and Hitherto Unobserved Phenomena of Binocular Vision,”

June

21, 1838

2 Ibid.,

page 376

3. Holmes,

Oliver Wendell. “The Stereoscope

and the Stereograph”, Atlantic Monthly,

June, 1859, pages 738-739

4. Julesz, Bela “Foundations of Cyclopean Perception”,

Univ. Chicago Press, 1971

5. Krause, E.E., Reading in 3-D, Research and

Development, Nov. 1972, pages 38-40

6. Layer, H.A., Space Language: Three Dimensional Concrete Poetry, Media and

Methods,

January 1972

7. Holmes, Oliver Wendell, “Sun Painting and Sun

Sculpture,” Atlantic Monthly,

July 1861 pages 14-15

8. Brewster, D., The Stereoscope; It’s History, Theory and Construction with

its

Application to the Fine and Useful Arts

and to Education, London: John Murray,

1856, Chapter VI, page 91

9 Layer, H.A., Exploring Stereo Images: A changing awareness of space in the fine

arts, Leonardo 4 233, 1971

ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig.

1 Wheatstone’s Cubes, 1838

Fig 2 Stereoscope-Wheatstone,

1838

Fig 3 Wheatstone

– Original page of Stereo Constructions, 1838

Fig 4 Convergence

of Lines of Sight

Fig 5 Analysis

of the Binocular Disparity Field and Stereopsis

Fig 6 Parallel

Lines of Sight -- Crossed

Lines of Sight

Fig 7 Methods

– Theory

Fig 8 Stereoscopic

Advertisement, 1860

Fig 9 Psychic,

Cyclopean and Binocular Fields

Fig 10 N-Crystalographic Field of Wheatstone’s Line Figures

|

It remained for Wheatstone to make the singular

discovery that when we view a cube which is set before us and when we

close one eye and then the other, it is apparent that we see two distinctly

different appearances of the cube. While

corroborations of this fact can be traced back through illustrious writings

of Francis Agullonius, Baptista Porta, Leonardo Di Vinci, and even more

into the remote past—to Galen and Euclid, it remained for Wheatstone to

produce the first stereo- synthetic form and the means to achieve a conscious

stereopsis of it in the mind. It

must have been an extraordinary moment of insight when he realized that

when two outline drawings representing the binocular view of a cube might

become fused together, then this image would be accepted by the mind as

a concrete solid existing in the same real spatial sense—as though one

could reach out to touch it. Indeed

this was the case. Wheatstone devised a simple mirrored apparatus

to aid the cause of fusing his three-dimensional drawings. He called this device a Stereoscope

(Fig.2). Wheatstone does not appear

to discuss, at any length, the direct vision viewing of stereo pairs,

nor does he suggest that he has delivered to the visual arts a new revolutionary

method. He speaks to this, however,

in these words:

It remained for Wheatstone to make the singular

discovery that when we view a cube which is set before us and when we

close one eye and then the other, it is apparent that we see two distinctly

different appearances of the cube. While

corroborations of this fact can be traced back through illustrious writings

of Francis Agullonius, Baptista Porta, Leonardo Di Vinci, and even more

into the remote past—to Galen and Euclid, it remained for Wheatstone to

produce the first stereo- synthetic form and the means to achieve a conscious

stereopsis of it in the mind. It

must have been an extraordinary moment of insight when he realized that

when two outline drawings representing the binocular view of a cube might

become fused together, then this image would be accepted by the mind as

a concrete solid existing in the same real spatial sense—as though one

could reach out to touch it. Indeed

this was the case. Wheatstone devised a simple mirrored apparatus

to aid the cause of fusing his three-dimensional drawings. He called this device a Stereoscope

(Fig.2). Wheatstone does not appear

to discuss, at any length, the direct vision viewing of stereo pairs,

nor does he suggest that he has delivered to the visual arts a new revolutionary

method. He speaks to this, however,

in these words:

This will require some examination of our

binocular powers of vision. Two

distinctly different projections of outside environments, falling upon

the active retinal screens of both eyes cause the unexplainable, as yet

hidden, power of consciousness to form a coherent, corespondent synthesis

of the outside environment. When

we fix our eyes, in a relaxed manner, upon the most distant reaches of

a landscape, both eyes, are said to be staring with parallel lines of

sight. (Fig. 4) Each

eye, under these circumstances, is rendering its own different view of

what might be a line of mountains. We

may say that in the “mind’s eye” the images of the mountains have coalesced—fused

into one image; as though we had

an eye in the middle of our foreheads. In a sense, metaphorically, we have; we will refer to this as the

cyclopean eye. (Hering, “oeil de cyclope imaginaire,” 1867)

This will require some examination of our

binocular powers of vision. Two

distinctly different projections of outside environments, falling upon

the active retinal screens of both eyes cause the unexplainable, as yet

hidden, power of consciousness to form a coherent, corespondent synthesis

of the outside environment. When

we fix our eyes, in a relaxed manner, upon the most distant reaches of

a landscape, both eyes, are said to be staring with parallel lines of

sight. (Fig. 4) Each

eye, under these circumstances, is rendering its own different view of

what might be a line of mountains. We

may say that in the “mind’s eye” the images of the mountains have coalesced—fused

into one image; as though we had

an eye in the middle of our foreheads. In a sense, metaphorically, we have; we will refer to this as the

cyclopean eye. (Hering, “oeil de cyclope imaginaire,” 1867)

As

a further consequence of this discussion of disparity and convergence

it will help to look at Fig. 6 which illustrates the two distinctly different

methods of viewing binocular constructions. The method of parallel lines of sight

(staring fixedly ahead beyond the pairs) and the method of crossing

lines of sight are contrasted. Viewing

stereo constructions by means of parallel sight limits picture size (2

½” separation between image objects) which is a physical limitation based

upon the interocular separation of the eyes.

This special kind of vision, then, limits itself to small scale

pictures and figures. An interesting

example of the early use of this idea, published in 1860, is the advertisement

shown in Fig. 8. This example

serves to demonstrate the arrangement of words as merely decorative as

distinguished from the expressive-spatial interrelationship found in 3-D

Concrete Poetry. (6)

As

a further consequence of this discussion of disparity and convergence

it will help to look at Fig. 6 which illustrates the two distinctly different

methods of viewing binocular constructions. The method of parallel lines of sight

(staring fixedly ahead beyond the pairs) and the method of crossing

lines of sight are contrasted. Viewing

stereo constructions by means of parallel sight limits picture size (2

½” separation between image objects) which is a physical limitation based

upon the interocular separation of the eyes.

This special kind of vision, then, limits itself to small scale

pictures and figures. An interesting

example of the early use of this idea, published in 1860, is the advertisement

shown in Fig. 8. This example

serves to demonstrate the arrangement of words as merely decorative as

distinguished from the expressive-spatial interrelationship found in 3-D

Concrete Poetry. (6)  of

lines of sight that must draw our full attention.

This is of great importance because there is no limit to the

size of images and constructions; nor is there a limit to the distance

from which they may be viewed. Crossing

lines of sight is central to the proposal in this thesis.

It must be noted that both of these methods (parallel and cross

vision) of viewing stereo constructions have quite different properties. This difference will be apparent as you try

to view the constructions in Fig. 6.

You will note an inversion of the spatial figures if you use

one and then the other method of viewing the small figures. The large stereo drawing at the top of the page is impossible to

view with parallel sight because the homologous points are beyond 2

½ inches. With crossed vision

they present no problem. Accomodating

yourself to crossing your lines of sight brings the viewer to within

reach of the new space art—an art whose only

of

lines of sight that must draw our full attention.

This is of great importance because there is no limit to the

size of images and constructions; nor is there a limit to the distance

from which they may be viewed. Crossing

lines of sight is central to the proposal in this thesis.

It must be noted that both of these methods (parallel and cross

vision) of viewing stereo constructions have quite different properties. This difference will be apparent as you try

to view the constructions in Fig. 6.

You will note an inversion of the spatial figures if you use

one and then the other method of viewing the small figures. The large stereo drawing at the top of the page is impossible to

view with parallel sight because the homologous points are beyond 2

½ inches. With crossed vision

they present no problem. Accomodating

yourself to crossing your lines of sight brings the viewer to within

reach of the new space art—an art whose only requirement will involve the necessity of staring fixedly at the center

point between the dyptich images of a stereographic construction. (Fig.

7) There will be the essence

of hypnosis in the stare, for it will project one into space to interlock

with the painted color forms until he is no longer outside but virtually

inside—in aesthetic empathy with whatever visual forces have been unleashed

into the openness of space. The act of seeing this new space is simple: You, the viewer, may use a finger as a reference

to crossing your lines of sight, or you may block out the left and right

images with your hands; or use

the suggested cardboard block-out card shown in Fig. 7. You stare—you willfully converge your eyes

at your finger tip and at the same time observe the dual construction

requirement will involve the necessity of staring fixedly at the center

point between the dyptich images of a stereographic construction. (Fig.

7) There will be the essence

of hypnosis in the stare, for it will project one into space to interlock

with the painted color forms until he is no longer outside but virtually

inside—in aesthetic empathy with whatever visual forces have been unleashed

into the openness of space. The act of seeing this new space is simple: You, the viewer, may use a finger as a reference

to crossing your lines of sight, or you may block out the left and right

images with your hands; or use

the suggested cardboard block-out card shown in Fig. 7. You stare—you willfully converge your eyes

at your finger tip and at the same time observe the dual construction

It seems impossible that these words should

lie buried for 116 years. And

it is even more astounding that this marvelous description by Brewster

could possibly have been and still can be an art involving repeated patterns,

continuous friezes, whole architectural assemblages of crystalographic

color-forms suspended in air, existing beyond and beneath a dematerialized

planar surface. Buried in the

19 Century, and clearly within the scope of this statement—of the new

aesthetics, also lie experiments by Brewster, H. W. Dove, and O. N. Rood

on what they called the theory of “Lustre”. This involves the binocular fusion of color

fields giving rise to phenomenological kinds of atmospheric, optical color

mixture. The monocular color fields

of Seurat and color field abstractionists today will pale before the new

possibilities of binocular color fusion.

Returning to Brewster, one cannot underestimate the enormous possibilities

suggested by him. Not only is

he saying that the surface has dematerialized, but that stereoscopically

paired graphic forms can be multiplied n-times-in all directions.

In Fig. 10, one of Wheatstone’s paired drawings has been organized

as a potentially n-crystalographic field—either by the method of parallel

sight or by cross-viewing, you will immediately witness something very

astonishing: One will find that his “Cyclopean” sense, the unconscious, (Gestalt)

or whatever it will eventually be understood to be, will hold the entire field fixated while at the same

time, he (the viewer) is free to direct his eyes to any portion of the

field—to focally converge upon any particular isolated point, figure or

cluster of figures. How does

the mind hold so large a psychic field of visible forms constant

while permitting a foveal examination of details in any direction? It is as though one has induced hypnosis to one level of mind while

permitting another level of mind virtual license.

It seems impossible that these words should

lie buried for 116 years. And

it is even more astounding that this marvelous description by Brewster

could possibly have been and still can be an art involving repeated patterns,

continuous friezes, whole architectural assemblages of crystalographic

color-forms suspended in air, existing beyond and beneath a dematerialized

planar surface. Buried in the

19 Century, and clearly within the scope of this statement—of the new

aesthetics, also lie experiments by Brewster, H. W. Dove, and O. N. Rood

on what they called the theory of “Lustre”. This involves the binocular fusion of color

fields giving rise to phenomenological kinds of atmospheric, optical color

mixture. The monocular color fields

of Seurat and color field abstractionists today will pale before the new

possibilities of binocular color fusion.

Returning to Brewster, one cannot underestimate the enormous possibilities

suggested by him. Not only is

he saying that the surface has dematerialized, but that stereoscopically

paired graphic forms can be multiplied n-times-in all directions.

In Fig. 10, one of Wheatstone’s paired drawings has been organized

as a potentially n-crystalographic field—either by the method of parallel

sight or by cross-viewing, you will immediately witness something very

astonishing: One will find that his “Cyclopean” sense, the unconscious, (Gestalt)

or whatever it will eventually be understood to be, will hold the entire field fixated while at the same

time, he (the viewer) is free to direct his eyes to any portion of the

field—to focally converge upon any particular isolated point, figure or

cluster of figures. How does

the mind hold so large a psychic field of visible forms constant

while permitting a foveal examination of details in any direction? It is as though one has induced hypnosis to one level of mind while

permitting another level of mind virtual license.